Disruption for Doctors 2: Healthcare Examples

Recap of part I: disruptors are worse, not better

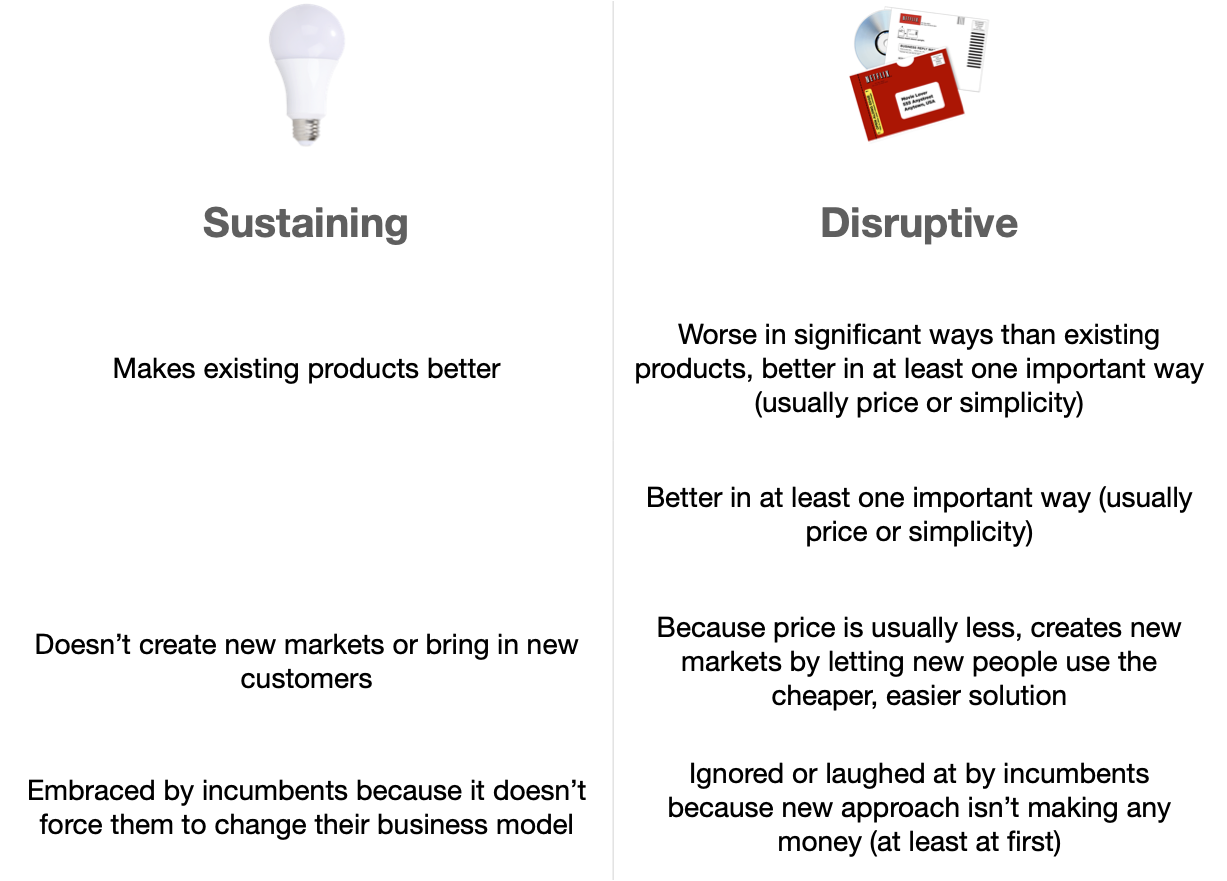

In my last post, I introduced the concepts of innovation developed by Clayton Christensen of Harvard. In Christensen’s paradigm, “sustaining” innovation enables incumbent organizations to better please their existing customers, while “disruptive” innovation weakens incumbents by creating new markets with cheaper but arguably worse technology.

As an example of “worse” disruptive technology, I talked about Netflix, which originally sent customers DVDs by postal mail. That seemed ridiculous to many who liked being able to just walk into a Blockbuster video store and then walk out with a video in a short time.

And the incumbents at Blockbuster apparently laughed and laughed . . . but Netflix was able to siphon off Blockbuster customers who were more price-sensitive. Then, when Netflix adopted streaming technology, they took all the remaining customers because at that point they were both cheaper AND faster.

But healthcare is not video streaming, so what about some examples of disruption in healthcare?

Non-IT-based healthcare disruption

There has been a lot of disruption within healthcare in the last decades; with some of it mostly related to information technology (IT) and some not. Let’s look first at some of the non-IT stuff.

Some examples:

doctors getting disrupted by ancillary providers like nurse practitioners, who have many fewer years of expensive training, and are paid less

primary care clinics and emergency departments getting disrupted by urgent care centers with a limited menu of services, and without the legacy costs of giant hospital-centric systems

specialists getting disrupted by other specialists (see next section, below)

Note that, as with our Netflix example, the disrupters are arguably worse in certain ways than the doctors they are trying to replace (sorry, “augment” 🤣). It’s hard to argue, for example, that nurse practitioners are better than primary care doctors. The important thing, however, is that they are good enough for some section of the patient population — and that they are cheaper.

Also, although these disruptive innovations aren’t mostly related to IT, they are dependent on the IT innovations of the last 40 years: it wouldn’t be so easy to run an efficient urgent care center without inexpensive personal computers, etc.

Example of non-IT healthcare disruption: heart disease treatment

Back in 2000, in an article entitled “Will Disruptive Innovations Cure Health Care?” Christensen himself provided an example of healthcare disruption. He and his coauthors talk about coronary angioplasty (or PCI, for “percutaneous intervention”), which enabled cardiologists to treat heart disease patients by inserting tiny tubes called stents into blood vessels — instead of requiring cardiac surgeons to perform cardiac bypass grafts (CABG). This is disruptive technology, for sure, and it’s a good illustration that disruptive technology doesn’t have to be information technology.

PCI didn’t eliminate heart surgeons, of course, but it did drastically reduce their activities: between 2001 and 2008, the annual rate of CABG in the US went down by 30%! So the incumbents (cardiac surgeons) lost a lot of revenue to the disruptive practitioners (interventional cardiologists) doing the PCI.

Keep in mind that CABG operations were, and are, better in certain circumstances but the disruptive PCI was generally cheaper because cardiologists are cheaper than cardiac surgeons, and PCI can often be outpatient. So the general idea of “disruption by worse, but cheaper” holds for this example.

The latest disruptor?

Interestingly, more recent data to 2016 demonstrated a roughly 40% decrease in both CABG and PCI — possibly due to more effective medicines (like statins and beta-blockers) reducing the need for surgery. So perhaps medical treatment for heart disease is now disrupting PCI, which previously disrupted CABG? Which might shift revenue back to primary care providers, whether doctors or nurse practitioners or other.

IT-based healthcare disruption

Disruptor of many things

The reason that nowadays we focus on IT when we think about disruption is that for about 40 years, most business disruption in the world has been driven by the IT revolution (further reading: Why Software is Eating the World).

Think about the efficiencies and cost savings made possible by the PC, the internet, cloud computing, and the mobile phone.

Now think about the fact that healthcare has really only adopted one of those innovations: personal computers. Ouch.

Which means that companies that are very, very good at IT are turning their attention to healthcare to see if they can begin picking off the low-hanging fruit from set-in-their-ways old-school health systems. And this includes those using the very latest technology: artificial intelligence (AI).

Some examples:

efficient lower-overhead systems (like Walmart Health) disrupting hospital-based systems (AND the urgent care companies!) with lower-cost systems that provide only the most commonly-needed services, and that can leverage their enormous portfolio of existing stores for office space. Also remember that Walmart got to be Walmart by being really good at IT (for supply chain management): we can expect efficiencies that most hospital systems can’t approach.

deep-pocketed tech companies, like Amazon Care, disrupting primary care by using tech to run clinics at lower cost. How can Amazon be successful? By using the same online tools they use as the biggest online retailer in the world and, less well known to the public, as one of the leading providers of cloud computing services to other tech companies, via their AWS division. And they are on a healthcare spending spree lately, having just purchased One Medical [Note: the day after publishing this, Amazon announced they’re shutting down Amazon Care and focusing on One Medical].

AI-based tools pulling some services away from expensive specialists, with one example being IDx-DR (see next section, below).

These IT-based disruptors are trying to use IT to create simpler, easier to use, cheaper versions of existing healthcare services.

Example of AI disruption: IDx-DR

Digital Diagnostics is a company based in Coralville, Iowa, far from tech centers like Silicon Valley or Boston. Using artificial intelligence computer vision techniques, they’ve built IDx-DR: the “first and only FDA authorized AI system for the autonomous detection of diabetic retinopathy.”

Translated, that means they have a machine that can take pictures of your retina and determine if you have diabetic retinopathy (DR, a debilitating problem that often occurs in poorly controlled diabetes).

Before IDx-DR, the only way to diagnose DR was for a very highly-trained and highly-paid ophthalmologist to look at your eyes. With Idx-DR, the diagnosis is automated and requires no input from any doctor, much less an expensive specialist.

This is the first machine capable of making a medical diagnosis by itself, and according to the website is “now part of the American Diabetes Association’s Standard of Diabetes care”.

Interestingly, it is marketed as a tool for primary care clinics, who can now avoid sending diabetic patients to expensive ophthalmologists for this diagnosis. That is a boon to primary care docs (and their patients) — but with 37 million diabetics in the US alone there is no real technological reason why this shouldn’t eventually find its way to a drugstore near you, right next to that automated blood pressure cuff.

Example of AI disruption: ChestLink

Another great example of AI-based disruptive innovation has been developed by Oxipit. Their ChestLink app, which is approved by European regulators but not yet the FDA, uses AI to read chest x-rays. It is apparently sensitive enough to identify the presence of problem, but not (yet) as good as a human radiologist to identify what the specific problem is.

ChestLink’s main use, as a result, is to automate the reading of the up-to-80% of chest x-rays that are normal, freeing up radiologists to focus on those images flagged by the software as suspicious. Note again that the software isn’t necessarily as good as a radiologist in identifying a specific problem, but it is good enough for a very common task that takes up a lot of human radiologist time.

How is this disruptive? Well, because using the software to verify x-rays as normal is so much cheaper than using a radiologist for the same purpose:

rich countries with radiologists won’t need as many, so the cost of this one small facet of healthcare (i.e. reading chest x-rays) will go down.

in poor countries, the software isn’t competing against radiologists, it is — in Christensen’s terms — competing against “non-consumption.” It can thus create a new market for the use of chest x-rays, bringing that beneficial medical technology to many more people.

From https://oxipit.ai

From specialists to generalists, from physicians to nurse practitioners, from hospitals to supermarkets

In Christensen’s 2000 article (echoed later in his 2016 book The Innovator’s Prescription) Christensen presciently wrote about many of the now-established trends in healthcare:

We need diagnostic and therapeutic advances that allow nurse practitioners to treat diseases that used to require a physician’s care, for example, or primary care physicians to treat conditions that used to require specialists. Similarly, we need innovations that enable procedures to be done in less expensive, more convenient settings—for doctors to provide services in their offices that used to be done during a hospital stay, for example.

All of this, of course, is commonplace in the healthcare of 2022: urgent care centers staffed by nurse practitioners, outpatient surgicenters, more techs working throughout healthcare.

But Christensen wrote that in the world of 2000: Google was 2 years old, AI was still frozen in a decades-old “winter”, and the iPhone existed only in the mind of Steve Jobs. The advent of two decades of consumer technology has not only accelerated the healthcare changes that Christensen envisioned, but also accelerated something he doesn’t seem to have thought much about: selfcare. That is, the ability of the consumer to treat their own illness, and to maintain their own health.

And in my next post, I’ll talk about healthcare moving not from doctors to nurse practitioners, but from nurse practitioners to . . . us.

Stay tuned.